The human immune system is a sophisticated network of cells and organs designed to defend the body against infection and disease. At the heart of this system are lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell that identifies and neutralizes foreign invaders. However, when the genetic programming of these cells malfunctions, the result is lymphocytic leukemia a cancer that originates in the bone marrow and rapidly crowds out healthy blood cells. For patients facing high-risk or relapsed forms of this disease, standard chemotherapy may not be enough. In these critical scenarios, STEM CELL Lymphocytic Leukemia protocols offer a potential lifeline, utilizing the power of cellular regeneration to overhaul the body’s defective defense system.

The Pathology of the Lymphoid Line

To understand the necessity of a transplant, one must first grasp the mechanics of the disease. Lymphocytic leukemia is broadly categorized into acute (ALL) and chronic (CLL) forms, depending on the speed of progression and the maturity of the cells involved. In both cases, the bone marrow produces an excessive number of abnormal lymphocytes, known as lymphoblasts in the acute form.

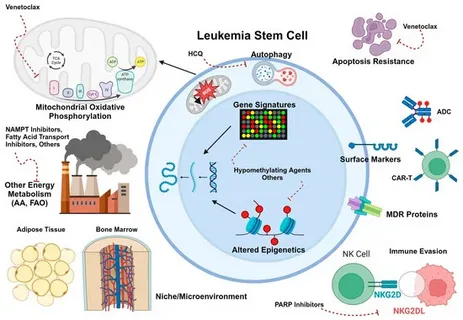

These malignant cells do not function correctly; they cannot fight infection effectively. Worse, their rapid proliferation occupies the physical space within the bone marrow, preventing the production of red blood cells (leading to anemia) and platelets (leading to bleeding risks). While chemotherapy agents are potent at killing these dividing cells, they often fail to eliminate the microscopic, dormant “leukemia stem cells” that can cause the cancer to return.

The Transplant Decision: A Strategic Reset

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is considered a curative approach for high-risk lymphocytic leukemia. It is not merely a treatment but a complete replacement of the blood-forming organ. The procedure is typically reserved for adult patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) who have adverse genetic markers, or for those who have relapsed after initial treatment. In Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL), which often has a slower course, transplantation is generally considered for patients with aggressive disease features (such as 17p deletion) that do not respond to targeted therapies.

The goal of the transplant is twofold:

- Myeloablation: To allow the administration of high-dose chemotherapy and total body irradiation (TBI). This intense conditioning regimen destroys the leukemic marrow entirely, creating a “clean slate.”

- Immunotherapy: To replace the patient’s immune system with that of a healthy donor.

The Allogeneic Advantage

For lymphocytic leukemia, the preferred method is almost exclusively allogeneic transplantation. This involves harvesting stem cells from a donor a matched sibling, an unrelated volunteer, or a haploidentical (half-matched) family member.

The choice of an allogeneic donor is driven by the “Graft-versus-Leukemia” (GVL) effect. Because the donor’s immune cells are genetically distinct from the patient’s, they can recognize any surviving leukemia cells as foreign and attack them. This biological surveillance is the most potent weapon against relapse and is unique to allogeneic transplants. Autologous transplants (using the patient’s own cells) lack this GVL effect and are rarely used for ALL due to the high risk of reintroducing cancerous cells.

Clinical Execution in Specialized Centers

Executing a stem cell transplant requires an infrastructure of high precision. The process begins with the conditioning phase, where the patient’s existing marrow is ablated. Following this, the donor stem cells are infused into the bloodstream. These cells navigate to the hollow cavities of the bones, a process called “homing,” and begin to rebuild the blood system.

Institutions like Liv Hospital play a pivotal role in this journey. The management of a transplant patient requires a multidisciplinary team capable of navigating the complex immunology of the procedure. From high-resolution HLA typing to ensure the best possible donor match, to the management of post-transplant complications, the expertise of the hematology unit is the determining factor in patient outcomes.

Navigating the Risks: GVHD and Infection

The introduction of a new immune system is not without peril. The most significant complication is Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD), where the donor’s immune cells attack the patient’s healthy tissues, such as the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Physicians must carefully modulate the immune system using immunosuppressive drugs to prevent severe GVHD while maintaining enough activity to preserve the Graft-versus-Leukemia effect.

Additionally, the period immediately following the transplant before the new cells engraft leaves the patient vulnerable to severe infections. During this time, patients are isolated in HEPA-filtered environments and monitored closely for any signs of fever or instability.

A Holistic Path to Survivorship

Recovery from a stem cell transplant is a transformative process that extends well beyond the clinical setting. The “new” immune system requires months to mature, necessitating a lifestyle of careful hygiene and nutritional support. Patients often face physical fatigue and emotional adjustments as they reintegrate into daily life. This phase of survivorship is about rebuilding not just the blood, but the whole person. Integrating balanced nutrition, mental resilience, and gradual physical conditioning is essential for long-term health. For those navigating this delicate transition, resources such as live and feel provide guidance on holistic wellness, offering insights into how to nurture the body and mind as they reclaim their vitality.