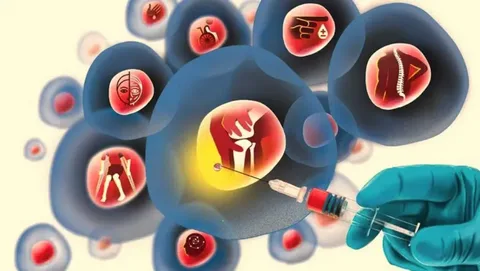

The human body relies on a relentless, unseen production line to sustain life. Deep within the cavities of our bones lies the bone marrow, a spongy tissue that functions as the body’s primary blood cell factory. Every second, millions of new blood cells are born here: red blood cells to carry oxygen, white blood cells to fight infection, and platelets to stop bleeding. However, for patients suffering from Bone Marrow Failure Syndromes (BMFS), this vital factory shuts down. The resulting silence is not peaceful; it is a life-threatening medical emergency. In these critical scenarios,STEM CELL Marrow Failure treatments offer a definitive lifeline, moving beyond temporary symptom management to restore the body’s fundamental ability to sustain itself.

The Pathology of Silence

To understand marrow failure, one must first visualize hematopoiesis, the process of blood cell formation. It begins with a single, multipotent “mother” cell known as the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC). In a healthy individual, these stem cells differentiate into various blood lineages. In marrow failure, the HSC population is either depleted, damaged, or genetically defective.

The clinical consequence is pancytopenia, a dangerous reduction in all three major blood cell types. Patients present with profound fatigue and pallor (due to anemia), frequent and severe infections (due to neutropenia), and unexplained bruising or bleeding (due to thrombocytopenia). Unlike leukemia, where the marrow is often overcrowded with cancer cells, marrow failure is frequently characterized by “aplasia” , an empty marrow where the vibrant cellular landscape is replaced by fat cells.

Classifying the Failure: Acquired vs. Inherited

Medical science categorizes these syndromes into two distinct groups, each requiring a tailored approach.

Acquired Bone Marrow Failure The most common form is Severe Aplastic Anemia (SAA). In the majority of these cases, the failure is autoimmune in nature. The patient’s own immune system, specifically T-lymphocytes, mistakenly identifies the stem cells as foreign invaders and destroys them. Other acquired causes can include exposure to toxins (such as benzene), radiation, viral infections (like hepatitis or EBV), or rare reactions to medications.

Inherited Bone Marrow Failure Syndromes (IBMFS) These are genetic disorders often diagnosed in childhood, though they can present in adults.

- Fanconi Anemia: A defect in DNA repair mechanisms leads to genomic instability and progressive marrow failure.

- Dyskeratosis Congenita: Associated with short telomeres (the protective caps on chromosomes), leading to premature cellular aging.

- Diamond-Blackfan Anemia: A failure specifically in red blood cell production. Diagnosis involves rigorous testing, including bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, as well as advanced genetic sequencing to identify specific mutations.

The Role of Stem Cell Transplantation

While supportive care such as blood transfusions and growth factors can keep a patient alive, they do not fix the underlying problem. For acquired aplastic anemia, immunosuppressive therapy (IST) is often the first line of defense to stop the immune attack. However, for patients who do not respond to IST, or for those with inherited syndromes where the stem cells themselves are genetically broken, Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT) is the only curative option.

The logic of the transplant is elegant in its simplicity: if the factory is broken, replace the machinery. By infusing healthy stem cells from a donor, physicians can re-seed the bone marrow. These new cells migrate to the bone cavities and begin the process of engraftment effectively building a new immune and blood-forming system from scratch.

The Critical Importance of Donor Matching

Success in transplantation for marrow failure hinges on finding the right donor. Because the goal is to replace the immune system, the donor’s tissue type, specifically their Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) must match the patient’s as closely as possible.

- Matched Sibling Donor (MSD): This is the gold standard. A brother or sister has a 25% chance of being a perfect match.

- Matched Unrelated Donor (MUD): If no sibling is available, search algorithms scour international registries to find a genetic match.

- Haploidentical Donor: Advances in medical protocols now allow for “half-matched” transplants, typically from a parent or child, expanding the curative potential to nearly all patients.

Institutions specializing in complex hematology, such asLiv Hospital, employ high-resolution HLA typing to ensure the most precise match, significantly reducing the risk of rejection or complications.

The Transplant Procedure: A Clinical Reset

The transplant process is an intensive medical journey.

- Conditioning: The patient undergoes a preparatory regimen. In marrow failure, this is distinct from leukemia treatment. The goal isn’t just to kill cancer, but to suppress the patient’s remaining immune system sufficiently to accept the new cells. This often involves chemotherapy and antibody therapy (ATG).

- Infusion: The healthy stem cells are infused into the bloodstream.

- The Nadir: Following conditioning, blood counts drop to near zero. This is the most vulnerable period, requiring isolation in HEPA-filtered rooms to prevent infection.

- Engraftment: Over the course of 2 to 4 weeks, the new stem cells settle and begin producing healthy blood cells.

Managing the Aftermath

Post-transplant care is a long-term commitment. The primary risk is Graft-Versus-Host Disease (GVHD), where the donor’s immune cells attack the patient’s healthy tissues. In marrow failure transplants, unlike leukemia, there is no benefit to this immune activity (no “Graft-versus-Tumor” effect is needed), so immunosuppression is managed carefully to prevent GVHD entirely. Long-term monitoring also focuses on organ function, particularly given the iron overload many patients experience from years of prior blood transfusions.

A New Chapter of Vitality

Surviving marrow failure is a testament to the resilience of the human body and the precision of modern medicine. As the new immune system matures, the restrictions of the illness fade. The fatigue lifts, the need for transfusions vanishes, and the patient steps back into a life of possibility. This transition from survival to thriving is the ultimate goal. Embracing a holistic approach to health prioritizing nutrient-dense foods, mental resilience, and physical rehabilitation ensures that the body is supported in its renewal. By engaging with resources that encourage them tolive and feel grounded and energized, survivors can fully reclaim their independence and look forward to a future defined by vitality rather than limitations.